Search Site

Back to Menu

The State of Port Warehouse Logistics

1. Introduction

Maritime & Ports Landscape in U.S.

Traditionally, and pre-pandemic, major U.S. ports operated on a scale to meet and deliver a smooth flow for the supply chain. This was flipped on its head from Q1 2020 into 2022. The widespread impact created by the ongoing ripple effect of the pandemic drove retailers and logistics providers to seek drastic changes and re-initiate their transportation planning and capacity management strategies.

In terms of volume, the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach dominate. However, many smaller ports across the United States also contribute to global trade’s lifeblood. The types of ports are also further classified into their strategic locations, and their water depth also impacts the kinds of goods, activities and vessels they can cater to. Thus, no port is alike and differentiates itself from the others in every aspect.

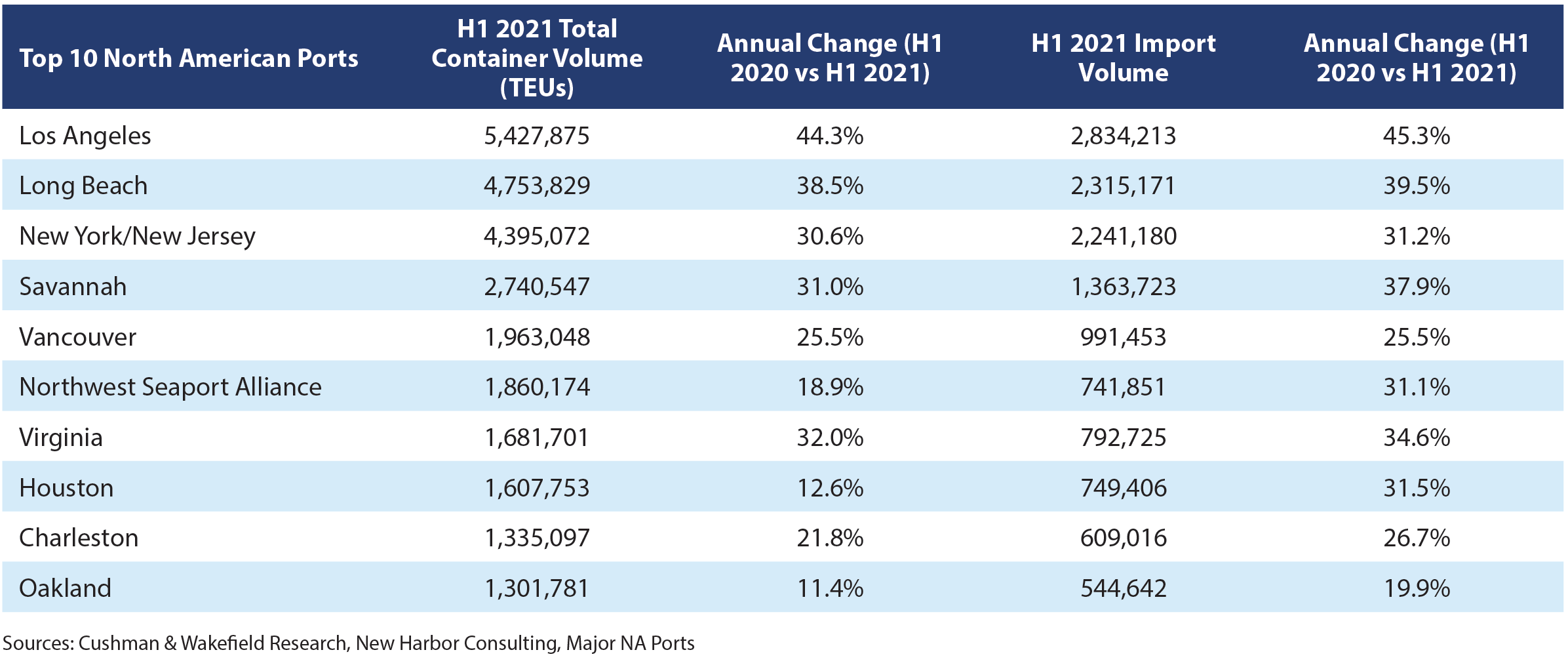

Ranking Among the Top North American Ports Mid-year 2021 (Jan-June)

CenterPoint Port Rankings 2022 Table

CenterPoint Port Rankings 2022 Table

2. The Ripple Effect of the Pandemic

As Scott Moorad, COO – North America at Hillebrand Bev Pros, says, “There is a complete imbalance of the global supply chain of getting product from A to Z. We’ve seen the anchored cargo ships in the LA-Long Beach area with records breaking. We’ve seen an increase in that challenge in the New York-New Jersey area as well. This has caused companies to rethink how they’re importing product.”

Moorad further states, “80%+ of our spending in this country is around entertainment and travel, and when the pandemic kicked in, it basically shut down the economy.” This drove spending into other areas. This shift in consumer dynamics created a huge surge in purchasing in the U.S., and supply chains were not set up to deal with that level of consumer spending. Brian Kempisty, Founder of Port X Logistics, refers to the e-commerce wave and uptick as the “Amazon Effect,” which was well on its way before the pandemic but was exacerbated by COVID-19.

Kempisty says, “The subsequent rise in volumes of containers coming into the United States rose by approximately 20%. Twenty percent as a number in percentage seems small. However, what it translates into for a port is this: LA-Long Beach handle almost 1.5 million containers a month combined, on average. Another 20% is another 300,000 containers. In turn, additional resources are required: the crane operators to handle it, the local drivers, the over-the-road drivers and so on. That’s a lot of extra labor that is involved – just to move the 20% extra volume and an extra 300,000 containers.”

Stemming from the increase in container volumes, Kempisty points out, “real estate is one of the biggest problems that we have. When you look at LA-Long Beach specifically, our team took a helicopter ride over the ports. There’s simply nowhere to put the containers, with the result being they’re not operating at maximum efficiency because they’re having to move containers around into different piles, which they call ‘closed areas.’ And that additional volume has also made it very difficult for them to accept empty returns.”

This is confirmed by Matt Mullarkey, SVP of Strategic Projects & Planning at CenterPoint Properties. With the e-commerce boom, he says, “the crucial factor is between the dollar value of sales and the required warehouse space needed to fulfill those sales.” This is due mainly to the fact that “the fulfillment processes that had previously gone on in a brick-and-mortar store are taking place in a warehouse. Now picking and packing are taking place in some warehouses, whereas traditionally, you would go to the store, pick your goods off the shelf and pack them into your cart. All that now takes place in the e-commerce environment, in a warehouse with many employees and associates in that warehouse performing that function.”

Ronel Borner, SVP of Development at CenterPoint Properties, seconds Mullarkey’s points, stating “dynamics have been booming. There’s no other way to put it. I’ve never seen anything like this. The tried-and-true rules of industrial real estate development that you would try to follow have shifted. Everything is just out the window, and dynamics are totally different.”

As Kathleen DePrizio, Director of Marine and Terminal Operations at Hyundai Merchant Marine America, states, “it’s a double-edged sword with what’s going on right now. You have a chassis problem. You have a trucker or driver shortage. You have labor shortages. You have warehousing shortages. Issues are compounding on top of each other, which has led to the ripple effect in the industry at large.”

Not all ports have been impacted equally. The East Coast ports were more flexible and labor-centric, more accommodating to the free flow and seamless supply chain outlook. This was elaborated on by most of the respondents who manage and handle port operations. For example, Brian Kempisty points out the two main glaring gaps. “The chassis in LA-Long Beach are maintained by the terminals, which in turn are managed by the unions. When you take 10,000 containers out of the port and deliver them to various warehouses, those containers are empty. It’s been very difficult to engage those empty containers. They end up sitting in the truck yard, on the chassis on the wheels, meaning that those wheels are not available to go pick up the next import container, and that’s where the gridlock is coming in.”

“The chassis in LA-Long Beach are maintained by the terminals, which in turn are managed by the unions. When you take 10,000 containers out of the port and deliver them to various warehouses, those containers are empty. It's been very difficult to engage those empty containers. They end up sitting in the truck yard, on the chassis on the wheels, meaning that those wheels are not available to go pick up the next import container, and that's where the gridlock is coming in.”

One of the things that makes the West Coast ports in Seattle, Oakland and Los Angeles more challenging to work with is that you have to make a pickup appointment to get your containers from the terminal. Additionally, delivery appointments are required to deliver the cargo. Then, a third appointment is needed to return the containers to the port. Almost every container will hit a trucker’s yard once or twice, so the terminals are always congested.

Contrary to this, you don’t need an appointment to pick up or return your empty containers at ports on the East Coast, for example, in Savannah. So, that makes it much more fluid and much more productive for the drivers to do business.

3. The Use of Safety Stock

Among other factors, safety stocks have been a key strategy for many companies looking to offset the risks associated with getting product into the country. Andrew Schuler, Logistics Supervisor from Santa Monica Seafood, says his company used to carry a “40-to-50-day supply of everything.” However, he says leaders soon realized that wasn’t enough, as they were burning through their inventory quickly. In reaction to this, they extended to a 90-day supply of everything.

Additionally, as Ronel Borner, Senior Vice President of Development at CenterPoint Properties, points out, “the biggest challenge that we’re seeing from a number of importers is they need to get their product off the port property quicker. More specifically, the ocean carriers are reducing the amount of time they’re willing to give their clients to store imported materials onboard. We’re seeing high demand for logistics properties close to ports. Importers are saying, ‘I have nowhere to go with this stuff. I have to get it off the port property. Let me see if I can find some industrial warehouse space. Doesn’t even matter what the format, the size or the condition, even for a 12-to-18-to-24-month period, just to get it off for property and then figure out what to do with it.’”

Eugene Petrovsky, Director, Supply Chain at WineSellers, also mentions “safety stock or excess spare stock to be shipped and housed” made them ramp up their inventories. Additionally, they’ve “asked for extra payment terms from our suppliers.” At any given day, while running stock reports, he’s realized that they “have anywhere from 40 to 50 items that are constantly out – we just cannot keep in stock due to the demand.”

Matt Mullarkey, CenterPoint Properties’ SVP of Strategic Projects & Planning, equates this to the multiplier effect. “As we’ve learned, very, very painfully, in some cases, and acutely, since the pandemic, there needs to be a far greater degree of safety stock. In fact, we’re reversing a very long-term relationship, as the inventory to sales ratio was going down over 20 plus years, with companies running very lean supply chains. When you have disruptions, and you have supply chains that are this long and complex, it becomes clear to everyone that we need far, far more safety stock.”

According to Matt, adding up all those elements “at any level of final sales, you need far more stock on hand, whether it’s two times or three times as much. The industry is evolving to understand what the exact multiplier is.” He is convinced everyone needs far more warehouse space “to handle every dollar of e-commerce sales, which is growing rapidly.” He defines it as a simple equation: “If e-commerce grows 15% a year, you need two or three times the square footage to accommodate it. That will largely explain the drivers of demand for warehouse space.”

“At any level of final sales, you need far more stock on hand, whether it’s two times or three times as much. The industry is evolving to understand what the exact multiplier is.”

Michael Murphy, CenterPoint’s Chief Development Officer, agrees safety stock is a major demand driver for industrial real estate. “We’ve seen the paradigm shift from ‘just-in-time’ to ‘just in case.’ So, before 2020 or so, if you were a retailer holding inventory, and you needed to change that inventory because the consumer wanted something different, you could reorder. Well, now, with the cycle time being what it is, you must have the product already on hand. I would think it’s virtually required now that most of the big retailers double what their inventory was just a few years ago. That means they’re having to warehouse more product. So, again, consumer demand is fueling the need for more warehouse space and more inventory control.”

Companies are seeking a competitive advantage, according to Mullarkey, by co-locating warehouses near where their containers arrive Stateside, further intensifying demand for industrial space. “You’re going to want to co-locate where all your containers are arriving. Tenants – major retailers and major 3PLs – have done their own math and determined ‘we’d rather be a mile down the street from where all our containers are arriving, to be able to go get them as necessary rather than be 50-100 miles away. That journey is a big source of lead time, and a source of fuel and transportation costs, too.’”

For Brian Kempisty at Port X, there’s one other thing that is yet to hit. “An unintended consequence is that cash flow is going to become a major issue. For truckers that are outlaying these demurrage fees, for example, they can’t go pick up a container until their storage is paid. If there’s $10,000 due in storage, that means, in many instances, we have an outlay of $10,000 on our customer’s behalf for the availability to make an appointment to go and get that container. Then it’s trucked to a destination in another state, but we’re holding that empty for 60 days. And we can’t return it, so we outlay $10,000. We traded it, transloaded it, trucked it into another city, had to hold the empty for 60 days, and we cannot invoice the customer until the empty is in gated, to know all the final charges for yard storage and chassis. Your normal, traditional 30-day payment terms could easily become 90- or 120-day payment terms.” For members of the trucking community, it’s very important they manage their cash flows responsibly.

Secondly, these additional fees and longer wait times all end up with the importers and retailers. If you’re paying a contract manufacturer in Asia to make your product and you’re in St. Louis, Missouri, you used to get it in 35 days and now you’re getting it in 90 days, and then you might miss the retail season. With 100 containers still waiting in the sea, they will likely miss sales this year and then the stock must be stored for an entire year.

4. Alternative Ports of Entry

An additional strategy that shippers are using to navigate these challenging times is to consider other ports of entry. Kirk DeJesus, Executive Director from the Port of Stockton, mentions the strife in the Ports of LA and Long Beach has meant that brands have looked at alternative ports of entry, such as the Port of Stockton. “We’ve probably benefited from the supply chain disruption. We’ve seen a 31% increase in our volume.”

According to DeJesus, the port’s California location has been advantageous. “In comparison to other ports like Oakland or Long Beach, which have deeper water so they can host larger vessels, Stockton has the benefit of having ample labor and consistent trucking, which has meant they haven’t seen cargo sit stale on the dock at all.” However, they have seen disruptions due to infrastructure issues, such as rail capacity, storage capacity and water depth. DeJesus emphasizes port officials’ focus is on now on improving the port’s rail infrastructure and its storage capacity, which has hit 99% in recent months.

CenterPoint’s SVP of East Coast Development, Ronel Borner, has seen smaller ports on the East Coast similarly benefit. “I think ports like the Port of Savannah that have capacity and have invested in long-term infrastructure projects to accommodate significant expansion of their activities have benefited from congestion at the larger ports. You look at the Port of Savannah in particular, and they are reaching new volumes this year that officials didn’t originally anticipate hitting until 2025, 2026. So, as a result, they’re accelerating other infrastructure projects that they weren’t anticipating putting into place until three, four years down the road to accommodate volumes in 2030. So, because of some of the backlog that we’ve seen in ports across the country, other alternative ports with great infrastructures have become beneficiaries.”

Furthermore, Bethann Rooney, Deputy Director of the Port of New York & New Jersey, highlights that even though the Port of N.Y. and New Jersey has had a cargo increase of 23% at their terminals, they’ve had the capacity to manage this. “The terminal operators have been focused on health and safety while keeping terminals operational with extra hours of operation on Saturdays,” and even expanding operations into night-time hours.

Rooney says the uptick of “extra hours has been minimal because there’s no room in warehouses, as containers are stuck in the marine terminals for two to three times more than usual. Average dwell time was 3-4 days, increasing on average to 8-12 days. Still, there have been containers that have been around for 30+ days, making the terminal an extension of the warehouse.” Due to the fees charged to keep the containers in the terminal, “some shippers have moved the containers from the terminal, but they still stay on the chassis.”

Some of the inputs Rooney highlighted have led to this success. “We had the capacity in the port as a result of billions in investments by the port authority and terminals. We have the forum on the council of port operators, which brings together executives of the industry across the entire supply chain. When they come to the table, they represent a sector – and not their employer – like warehousing [or] trucking, and everybody works together to come up with a solution for the good of the whole.” When experiencing congestion “the council – in order to ensure that the port would be resilient to any type of disruption in the future – provided the platform for coordination, collaboration, communication and transparency.” Earlier in 2020, the council used to meet on a quarterly basis. However, given the changing scenario, they decided to start meeting weekly.

According to Rooney, “communication, teamwork and transparency have been key to being able to handle this extra volume.” East Coast ports have experienced labor shortages, chassis issues, hurricanes, and equipment shortages, whereas the West Coast ports were going through lockout issues. On the chassis problem, Rooney adds, “We never implemented a chassis pool. We collectively decided we would remove them and centralize them in jointly operated yards, with assets remaining.” The recommendation led them to spending two years trying to implement it, during which they decided on a completely new structure which is now “touted as the model to follow.”

Despite the surge in volume in other ports (such as the Port of Stockton), many brands are facing ongoing challenges with seemingly no quick fixes. Scott Moorad, COO – North America at Hillebrand Bev Pros, says, “One of the things we haven’t talked about is the fact that the size of the cargo ships has grown immensely over the last 20 years. That drives better efficiency, but not all the terminals and ports are designed to handle them. There’s huge investment that has to happen, and there are not a lot of overnight successes.” For Hillebrand, “the core is still in the major ports, and they are constantly looking at alternatives, where there may be scope for offloading.”

Similarly, Eugene Petrovsky, Director, Supply Chain from WineSellers, Ltd., mentions trials with alternative ports have backfired. “We tried an alternate route and shipped to Port of Houston. Then we were going to rail the containers up to Oakland. However, that has backfired on us.” As their containers started arriving in Houston, there were “some issues with the weather, and then there was a brief period of time where Houston’s port networks went down.” This compounded the “main issue of this routing causing the rail systems to become overwhelmed.” Another reason for the failure of “the Houston experiments,” in Petrovsky’s words, was that “there was a shortage of truckers. Of course, there’s a shortage of chassis. Even when the containers were offloaded in Houston and even if they could get on rail, there was nobody to bring them onto the rail.” These shortages seem agnostic to any particular port.

Brian Kempisty from Port X says an alternate approach for the shipping industry is that “there’s one other item that no retailers really want to hear, and I’ve been encouraging people to palletize their cargo overseas. Many of these containers in vessels coming in now must be transloaded. So, we pick them up from the port, we bring them back to our warehouse, we translate them to over-the-road trucks and then maybe deliver them to Chicago or Atlanta or Dallas. It takes nine man-hours to translate 1000 cartons on the floor into a trailer. This means three guys for three hours, and you’re tying up the container in one dock for three hours in the trailer and another dock for three hours. If you palletize your cargo overseas, you have one man on a forklift, and it’s 45 minutes versus the nine man-hours that it took. Most retailers and importers do not want to hear that because they lose a little bit of capacity in the container from overseas. But, with our U.S. infrastructure for drayage, transloading and trucking at gridlock now, if you can get better velocity through the supply chain – better use of drivers and warehouses – we could get this thing cleaned up in a quarter of the time make it way faster.”

If you can do four times as many transloads in a day, you’re getting four times as much cargo out of the port and on the road to Distribution Centers for final consumption. “It’s that velocity and more efficient use of our equipment and drivers we need to strive for, especially with labor as an issue.”

Likewise, 90% of the drayage drivers in L.A/Long Beach are owner-operators, and owner-operators do not get paid by the hour. They get paid by the move. Hence, drivers are getting very frustrated when their efficiency goes down. Because if you could do more moves in a day, you would get paid more. “This velocity is very important for the drivers as well to make money and stay in the business,” said Kempisty.

Furthermore, Kempisty added, “it would be way easier and more cost-effective to pay somebody in China or Vietnam to put the cargo on pallets than somebody in the United States. From a labor cost perspective, it would be way cheaper for these retailers in the long run. This cargo is almost always palletized at some point through the supply chain, so why not just get it done overseas?”

A simple but useful exercise prescribed by Sanjeev Sahani, VP of Operations at Wayfair, is to think about the journey. “People don’t necessarily always think through the journey a container takes from the time it gets off a ship to the time it makes it to a warehouse. Then, actually working through the choke points, interestingly, you will find that it’s not a common issue in every single port. There are some ports which are phenomenal at managing unload times from the vessels. There are ports which are great in creating stacks for the end consumer, and for the retailer bringing those in.” But the “interfaces with the truckers or the interfaces with the customs logistics agencies may be an issue for them. And for the others, it may be the exact opposite.. Generalizing ports disruption – strife and backlogs – sometimes takes you away from the real problem at hand, which actually is fairly more complicated than it seems.”

For Sahani, “the investment needs to go in the steps that will improve our productivity and efficiency of ports. That is where we need to prioritize investments and work that needs to be done.” Wayfair continues to make end-to-end technology and analytics investments to predict when they think their containers and their goods become available and how they use that information to satisfy the end customer truly. Not unsurprisingly for a tech firm, the kinds of investments Wayfair is making are typically in data science and models, which focus on historical data and trends of the performance of certain shipping lines, ports, clearance timelines and trucking companies. This data is then input into various data science models to derive what should be the prediction for clearing every single one of the items from any particular vessel.

Another major factor, according to Sahani, “is collaboration in the supply chain, but it comes down to this: are we sharing data with each other? Prioritization of where data sharing happens is the first element to solve. Typically, data sharing is actually less valuable than what really makes the difference.” What they have learned in their initial collaboration efforts was that “what really matters is your choke points, and how you use the data within the choke points and the parties that are involved.”

Technology, as an investment and an enabler, has come to the rescue of quite a few shippers. As Scott Moorad stresses, “the investment that we are doing, and the demand of our customers is to generate greater visibility. Real-time visibility is much more necessary because you’re really trying to manage your inventory and your demand planning”. For him, “when everything was just flowing and working more smoothly, yes, you wanted visibility, but you could just assume where it was. Now you need to know because you can’t trust where it’s at.”

5. Conclusion

The solutions to alleviating supply chain pressures – improving shipping efficiency, lessening the time from manufacturing to doorsteps, reigning in and controlling mounting transportation costs, keeping the cost of goods in check for consumers and maintaining and enhancing profitability for e-commerce companies and their service providers – are varied and can even seem daunting. Infrastructure improvements such as port upgrades that can provide long-term relief and stability are costly and complex. They require tremendous cooperation between public and private institutions and take years to execute and bear fruit.

Analysts agree e-commerce activity and the far-flung impact it has on a vast array of industries is here to stay – even if it never again matches the mind-boggling 40%+ increase we saw at the height of the pandemic – and the crunch surging online sales has placed on shippers shows few signs of dramatically ebbing in the foreseeable future. For e-commerce companies, port operators and distributors, their focus promises to remain firmly on finding ways to absorb and develop high-throughput industrial real estate as a critical supply chain component from the first to the last mile. Whether the supply chain operates at optimal levels and regardless of how companies integrate technology into their shipping platforms, the need for quality industrial space must keep pace with consumers’ thirst for more goods delivered faster. The so-called “space race” is virtually assured to be an omnipresent feature of the new e-commerce-fueled economy.

CenterPoint’s Senior Vice President of Development, Brian McKiernan: “What we’ve seen in recent years and certainly since the pandemic is that there is an obvious lack of national supply of industrial space. There are not enough warehouses to accommodate the level of e-commerce and supply and consumption that’s coming out of those warehouses, much less what will be needed in the years to come. So, I think that’s where we see this fundamental long-term change, and maybe it’s not a cyclical issue. It’s longer, maybe even something like a hundred-year-type concept. We’re seeing a lot of the smaller suppliers, a lot of 3PLs, looking at having a much longer-term and more sophisticated e-commerce strategy where, before, that sort of planning was much more germane to the top two, three, or five retailers and e-commerce providers.”

Sources

Subscribe

Microsite Request